In the United States, the federal legislative powers—the ability to consider bills and enact laws—reside with Congress, which is made up of the US Senate and the House of Representatives. This resource is designed to help you understand how this complex process works!

Introducing a Bill and Referral to a Committee

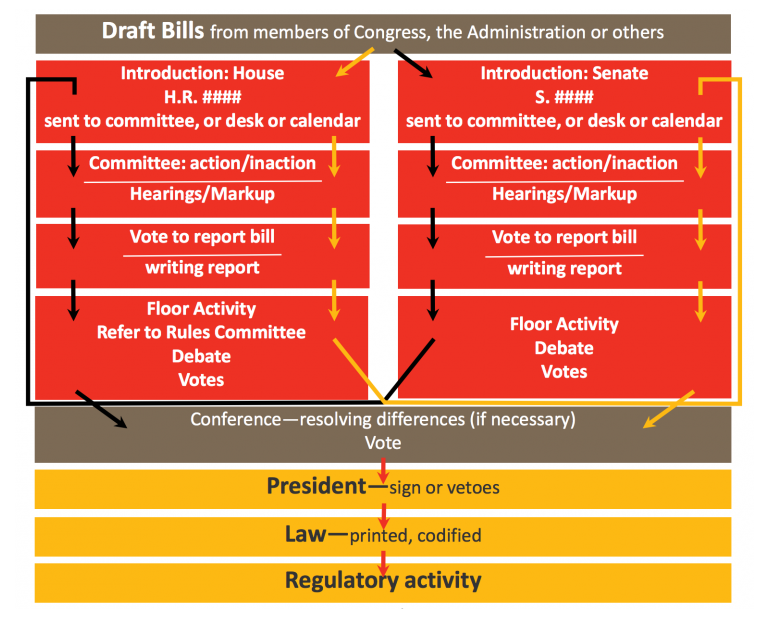

Any member of Congress can introduce legislation. The person or persons who introduce a bill are the sponsors; any member of the same body (House or Senate) can add his or her name as a cosponsor after the day of introduction. When a bill is introduced, it is given a number: H.R. signifies a House bill and S. a Senate bill. The bill is then referred to a committee with jurisdiction over the primary issue of the legislation. Sometimes a bill will be referred to multiple committees. And sometimes the bill is referred to a subcommittee first.

Committee Action: Hearings and Markup

The chair of the relevant committee determines whether there will be a hearing on the bill (which is an opportunity for witnesses to provide testimony) and then whether there will be markup, which refers to the process by which the proposed bill is debated, amended, and rewritten. Usually, a subcommittee holds the hearing, and then the bill can be marked up, first in subcommittee and then in full committee (although action can be taken only at the full committee level). After amendments are adopted or rejected, the chair can move to vote the bill favorably out of committee. If the committee favorably reports out the bill, it then goes to the entire body of the House or the Senate; if not, the bill essentially “dies” in committee.

Committee Report

The committee chair’s staff write a report of the bill, describing the intent of the legislation, the legislative history (such as hearings in the committee), the impact on existing laws and programs, and the position of the majority of members of the committee. The members of the minority, including the Ranking Member, (the most senior committee member from the minority party), may file dissenting views as a group or individually. A copy of the bill as marked up is usually printed in the Committee Report.

Floor Debate and Votes

The Speaker of the House and the Majority Leader of the Senate determine if and when a bill comes before the full body of the House and the Senate, respectively, for debate and amendment and then final passage. There are very different rules of procedure governing debate in the House and debate in the Senate. In the House, a representative may offer an amendment to a bill only if he or she has obtained permission from the Rules Committee. In the Senate, a senator may offer an amendment without warning, as long as the amendment is germane to the bill. In both chambers, a majority vote is required both for an amendment to be accepted and for the final bill to be passed, although amendments are sometimes accepted by a voice vote (in which individuals say "Yea" or "Nay,” and the loudest side wins; the names or numbers of individuals voting on each side are not recorded).

Referral to the Other Chamber

When the House or the Senate passes a bill, the bill is referred to the other chamber, where it usually follows the same route through committee and floor action. That chamber may approve the bill as received, reject it, ignore it, or amend it before passing it.

Conference on a Bill

If only minor changes are made to a bill by the other chamber, the legislation usually goes back to the originating chamber for a concurring vote. However, when the House and Senate versions of the bill contain significant and/or numerous differences, a conference committee is officially appointed to reconcile the differences between the two versions in a single bill. If the conferees are unable to reach agreement, the legislation dies. If agreement is reached, a conference report is prepared describing the committee members’ recommendations for changes. Both the House and the Senate must approve the conference report. If either chamber rejects the conference report, the bill dies.

Action by the President

After the conference report has been approved by both the House and the Senate, the final bill is sent to the President. If the President approves the legislation, he signs it and it becomes law. If the President does not take action for 10 days while Congress is in session, the bill automatically becomes law. If the President opposes the bill, he can veto it; or if the President takes no action and Congress adjourns its session, it is a "pocket veto" and the legislation dies.

Overriding a Veto

If the President vetoes a bill, Congress may decide to attempt to override the veto. This requires a two-thirds roll call vote of the members who are present in sufficient numbers for a quorum

Overview of the Legislative Process Video

(This video was originally published on the Law Library of Congress' website. To access a transcript of this video and additional accompanying materials, please visit the site here.)